A compelling exhibition is a rigorous visual argument, not a casual collection of an artist’s best work.

- The core of a powerful show is its ‘visual thesis’—a central, unifying idea that each piece of work serves to prove or explore.

- Effective curation uses ‘hero images’ as evidentiary anchors and intentional sequencing to create an emotional and intellectual rhythm for the viewer.

Recommendation: To elevate your work, stop thinking like a storyteller and start operating like a curator—using your images as evidence to build a cohesive and intellectually compelling exhibition.

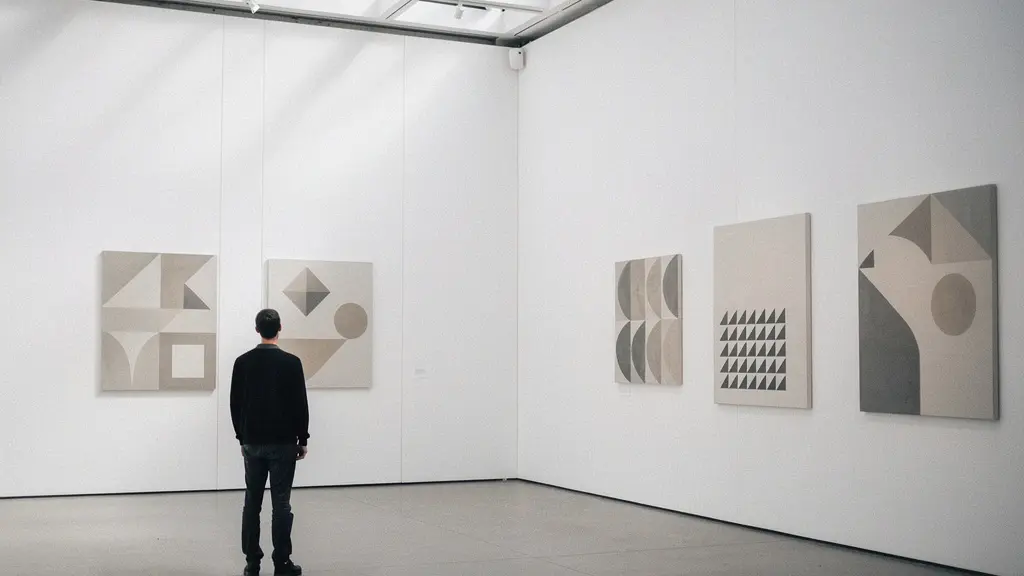

For many artists, the studio is a space of divergent exploration. The result is often a portfolio of technically proficient and aesthetically strong images that, when viewed together, feel disparate and disconnected. Faced with the opportunity of a solo exhibition, the challenge becomes monumental: how does one weave these scattered threads into a single, coherent tapestry? The common advice to “tell a story” or “select your best images” is profoundly inadequate. It treats the exhibition as a mere scrapbook rather than what it must be: a sophisticated, unified statement.

This approach mistakes sentiment for substance. A truly impactful exhibition does not emerge from a loose narrative; it is constructed upon a firm intellectual foundation. The process is less like storytelling and more akin to authoring a visual thesis. It requires a shift in mindset, from artist-as-creator to artist-as-curator. This means every choice—from selection and sequencing to the framing of the artist’s own biography—must serve to articulate and defend a central argument. The work must not only be seen; it must be understood as part of a larger, deliberate inquiry.

But what if the key to unlocking a powerful exhibition was not in finding a ‘story’ that fits your existing work, but in defining a rigorous ‘thesis’ that gives your work its ultimate purpose? This is the curatorial method. It provides a framework to justify the inclusion of every piece, to dictate their order, and to create an experience that resonates on an intellectual and emotional level. It transforms a collection of images into a body of work.

This guide will deconstruct the curatorial process, providing a clear methodology for developing and executing a strong thematic thesis. We will explore how to select anchor works, structure visual rhythm, and ensure conceptual integrity from the wall to the written word, ultimately transforming your disparate portfolio into a singular, commanding exhibition.

Summary: Developing a Strong Curatorial Thesis for Your Exhibition

- Why Do You Need “Hero Images” to Anchor a Visual Narrative?

- How to Order Your Images to Create Emotional Peaks and Valleys?

- Subject Matter or Visual Style: Which Binds a Series Better?

- The Repetition Error That Makes a Series Feel Monotonous

- How to Ensure Your Written Theme Matches Your Visual Output?

- How to Write an Artist Bio That Intrigues Collectors?

- When to Hire an Archivist to Catalog Your Growing Collection?

- How to Plan and Execute Your First Solo Photography Exhibition?

Why Do You Need “Hero Images” to Anchor a Visual Narrative?

In the construction of your visual thesis, not all pieces of evidence carry equal weight. A “hero image” is not merely your most technically perfect or aesthetically pleasing photograph; it is the primary articulation of your central argument. It functions as the abstract of a scholarly paper or the opening statement in a legal case—it encapsulates the core theme, sets the emotional tone, and provides the viewer with an immediate, potent entry point into the world you have constructed. Without this anchor, a viewer is adrift, left to piece together a theme from a sea of visual information, a task for which they may have little patience.

The hero image is a strategic choice. It must be emblematic of the entire series, possessing the conceptual DNA of the whole exhibition. It is the work that, if seen in isolation, would still communicate the essence of your project. This image will often be used for promotional materials, invitations, and as the lead image online, making its selection a critical curatorial decision. It must be strong enough to bear the weight of the entire narrative, acting as a recurring visual touchstone to which the viewer’s mind can return as they navigate the more nuanced or divergent works in the series. It’s the standard against which all other images in the exhibition are implicitly measured.

Your Action Plan: A/B Testing Framework for Hero Images

- Select 2-3 potential hero images that represent different facets of your theme.

- Test with a trusted, critical audience. The goal is to establish which image best communicates the core thesis and generates the desired emotional response. As a UNICEF photo editor notes, the key is finding the image with the ‘greater resonance with the personal narrative’ and establishing ‘a hero in a narrative’.

- Document viewers’ first impressions and emotional responses to each image. Ask them what they believe the series is about based on that single image.

- Analyze which image creates the strongest and clearest ‘entry point’ into your exhibition’s narrative, aligning most closely with your intended thesis.

- Consider placement and scale. Hero images often achieve maximum impact when printed at 1.5x to 2x the size of surrounding works, physically signifying their importance.

How to Order Your Images to Create Emotional Peaks and Valleys?

Once your anchor works are established, the curatorial task shifts to sequencing. A common mistake is to arrange works chronologically or based on a simplistic linear narrative. A sophisticated exhibition, however, is paced for emotional and intellectual rhythm. The goal is not to tell a story from A to B, but to guide the viewer through a carefully modulated experience of tension, reflection, intensity, and release. This is the art of creating emotional peaks and valleys.

A peak might be a large-scale, compositionally dense, or emotionally charged image that demands attention and provokes a strong reaction. A valley, in contrast, could be a quieter, more minimalist, or contemplative piece that offers the viewer a moment of respite and intellectual digestion. Arranging your work is like composing music; a relentless barrage of “peak” images leads to viewer fatigue, while an endless series of “valley” images results in monotony. The interplay between them is what creates a memorable and engaging journey. As the Art Business News Editorial on curation notes, “Too much uniformity, and the exhibit risks monotony. Too much disparity, and the theme loses clarity. The goal is to create a tapestry of artworks that, while diverse, speak to a harmonious narrative.”

This deliberate pacing controls the flow of energy within the gallery space. You can build tension by placing a series of increasingly complex images together, then break it with a single, starkly simple photograph. You can create a moment of profound insight by following a chaotic scene with an image of quiet solitude. This is not storytelling; it is psychological orchestration. Your sequence should feel intentional, guiding the viewer’s focus and emotional state from one frame to the next, reinforcing the central thesis with every transition.

Subject Matter or Visual Style: Which Binds a Series Better?

An artist with a scattered portfolio often defaults to one of two organizing principles: a recurring subject (e.g., “portraits of strangers,” “abandoned buildings”) or a consistent visual style (e.g., high-contrast black and white, a specific lens or film stock). While these can provide a superficial sense of unity, they are often insufficient for a truly compelling exhibition. A series bound only by subject matter can become repetitive, and one bound only by style can feel conceptually hollow. The most powerful binding agent is a third, more sophisticated element: conceptual intent.

Conceptual intent, or the ‘visual thesis’, is the underlying idea the work explores. It allows for variation in both subject and style, as long as each piece serves the central inquiry. This is the hallmark of mature, museum-quality curation. Consider the 2024 Venice Biennale’s theme, ‘Foreigners Everywhere.’ As described in an Artnet News report, curator Adriano Pedrosa focused on artists who were immigrants, exiles, and outsiders. The resulting exhibition was not bound by a single aesthetic or subject. Instead, it was unified by a powerful conceptual framework that explored the notion of the ‘foreigner’. Some works addressed this theme directly, while others, as Pedrosa noted, delved into more formal issues but with their own ‘foreign accent’.

This demonstrates how a strong conceptual bind creates a framework where diverse works can enter into a dialogue. The following table, adapted from an analysis of curatorial strategies by Art Business News, breaks down these approaches.

| Binding Element | Strengths | Challenges | Best Used When |

|---|---|---|---|

| Subject Matter | Immediately recognizable unity, easy for viewers to understand | Can become predictable if not varied in approach | Documentary projects, social issues, location-based work |

| Visual Style | Creates strong aesthetic cohesion, develops artistic signature | May limit conceptual exploration | Building artistic brand, formal explorations |

| Conceptual Intent | Works embody the concept and communicate with one another, creating visual and conceptual dialogue while allowing varying styles | Requires clear articulation to viewers | Museum exhibitions, intellectual explorations |

For the artist aiming to unify a disparate portfolio, the lesson is clear: look beyond the surface similarities in your work and identify the deeper, recurring questions or ideas. This conceptual thread is what will transform your collection of images into a cohesive, meaningful body of work.

The Repetition Error That Makes a Series Feel Monotonous

There is a fine line between rhythm and repetition, between a motif and monotony. A common curatorial error, especially for artists working within a strong visual style, is to mistake consistency for cohesion. Presenting a series of images that are too similar in composition, scale, and subject matter doesn’t create a powerful statement; it creates a flat, predictable experience that numbs the viewer’s perception. This is the repetition error: the failure to introduce sufficient variation to maintain engagement.

A strong series utilizes repetition intentionally, as a baseline from which to deviate. The viewer’s brain is a pattern-seeking machine. By establishing a visual pattern—for example, a consistent compositional structure across several images—you create an expectation. The curatorial power lies in knowing when and how to break that pattern. This “pattern breaker” is a work that deliberately deviates from the established norm in a meaningful way. Its power is derived entirely from its context within the series. Placed at a strategic point, typically around two-thirds of the way through a sequence, it re-engages the viewer, shatters complacency, and often introduces a new layer to the visual thesis.

Beyond a single pattern breaker, sophisticated curation employs a range of variations to avoid monotony. This can include alternating scale between expansive and intimate views, or inserting “sabbath images”—quieter, simpler works that provide visual and cognitive breathing room. These moments of rest are not filler; they are crucial for allowing the viewer to process the more complex works and reset their palate. The goal is to create a dynamic system where repetition establishes a theme, and strategic variation deepens its exploration.

Your Action Plan: Breaking Monotony Through Strategic Variation

- Establish your baseline pattern with 3-4 consistent works to create recognition for the viewer.

- Introduce thematic variations. As outlined in a guide for curators by theprintspace, these can be “social, political, philosophical, or aesthetic” variations, creating progressions that can be “linear, abstract, or subliminal.”

- Place a ‘pattern breaker’ work at the 2/3 point of your sequence for maximum impact and to reignite viewer attention.

- Vary the scale of your prints, alternating between intimate small works and expansive, immersive large-format pieces.

- Create breathing room with ‘sabbath images’—quieter, less demanding works that allow the viewer to process and reflect before moving on.

How to Ensure Your Written Theme Matches Your Visual Output?

The most sophisticated visual thesis can collapse under the weight of a poorly articulated artist statement. The written theme—whether in a statement, a proposal, or wall text—is not an afterthought. It is the verbal key that unlocks the visual argument. A frequent and fatal error is a disconnect between the two, where the text makes claims the images do not support, or uses vague, poetic language that fails to illuminate the work. This creates a crisis of intellectual integrity.

To ensure alignment, your writing must be as rigorous and selective as your image editing. The first step is to move from passive description to active analysis. A weak statement describes what the work *is* (e.g., “These are melancholic landscapes”). A strong statement explains what the work *does* or *investigates* (e.g., “This series investigates how post-industrial landscapes embody a form of societal melancholy”). This shift from adjective to verb forces clarity and ensures your theme is grounded in action and inquiry, concepts that are far easier to manifest visually.

The language you use must be a direct reflection of the visual evidence. If your statement speaks of “ephemeral light,” the images must demonstrate a masterful and specific handling of that light. If it claims to “challenge conventions,” the work must be genuinely unconventional. A practical test is to have a trusted peer read your statement and then view the work separately. If they cannot see the direct connection, your alignment has failed. Your written theme should function like a scientific hypothesis; the images are the collected data that proves, explores, or complicates it. Every word must be justifiable by a corresponding visual element.

How to Write an Artist Bio That Intrigues Collectors?

The artist biography is one of the most misused documents in the art world. Too often, it is a dry recitation of academic credentials, exhibition history, and technical processes—a curriculum vitae masquerading as a biography. While this information has its place, it does little to engage a collector or deepen their understanding of the work. A curatorial approach transforms the bio from a mere CV into a vital piece of interpretive material. As one curatorial guide suggests, you must ” frame the bio not as a CV, but as a ‘key’ or ‘legend’ that gives the collector a conceptual entry point into the artist’s world.”

A compelling bio should be tailored to the specific body of work being exhibited. It must connect the artist’s life, experience, or intellectual preoccupations directly to the visual thesis on display. It answers the question: “Why is *this* artist uniquely positioned to explore *this* theme?” This creates a narrative that adds value and meaning to the art itself. A collector is not just buying an object; they are investing in an artist’s vision and journey. The bio is the primary tool for articulating that vision.

Case Study: The Exhibition-Specific Bio Strategy of Harry Gamboa Jr.

For the LACP 2024 Annual Awards Exhibition, honoree Harry Gamboa Jr. demonstrated this principle perfectly. His general biography highlights his foundational role in contemporary Chicano culture and the Asco collective. However, for this specific exhibition, his bio was tailored. It focused on how he was revisiting his career-long themes—the “convergence of photography, natural forces, performance and group-based action”—by leading performers to create new, action-based portraits. This specific biographical detail provided a direct, conceptual entry point into the new work on display, framing it as the next logical step in his artistic inquiry rather than just another project.

To achieve this, be selective. Instead of listing every residency, choose the one that catalyzed the body of work in the show. Instead of mentioning a generic art degree, describe a specific line of philosophical inquiry you pursued that informs your current practice. Your bio should not be a comprehensive history; it should be a curated narrative that serves the immediate goal of connecting a collector, intellectually and emotionally, to the work in front of them.

When to Hire an Archivist to Catalog Your Growing Collection?

For an artist, the body of work is the primary asset. As a career progresses, this collection of “visual evidence” can become unwieldy, disorganized, and ultimately, inaccessible. Prints get misplaced, digital files become corrupted, and the crucial contextual information—dates, locations, editions, previous exhibitions—is lost to memory. This state of disorder is more than an inconvenience; it is a direct threat to your artistic legacy and a significant barrier to future opportunities. The decision to hire a professional archivist is a crucial step from being a practicing artist to managing a professional artistic enterprise.

Hiring an archivist is not a sign of vanity; it is a strategic investment in the longevity and value of your life’s work. An archivist does more than simply organize; they create a systematic, searchable, and permanent record of your output. This professional cataloging is invaluable for numerous reasons. It enables curators, gallerists, and researchers to easily review your work for potential exhibitions or acquisitions. It is essential for planning a retrospective, where locating specific works from different periods is paramount. Furthermore, a well-managed archive facilitates the identification of thematic patterns and conceptual threads across decades of production, often revealing insights that were not apparent to the artist at the time.

The need for an archivist is often indicated by specific “trigger points” in an artist’s career. When the administrative burden of managing your collection begins to impede the creative process, it is time to seek professional support. Recognizing these moments is key to preserving the integrity and accessibility of your work for years to come.

- You are planning a retrospective exhibition spanning multiple decades of work and need to locate key pieces efficiently.

- You find it difficult to locate specific works or provide their precise details when curators, collectors, or gallerists make inquiries.

- You want to identify and trace thematic or stylistic patterns across your entire career, but your current system is too disorganized.

- The process of loaning work for exhibitions has become overwhelmingly complex. A resource on exhibition planning highlights that the acquisition process requires intense coordination for loan terms, transport, insurance, and conservation, all of which an archivist can manage.

- You need to tag works with conceptual keywords for thematic searches, allowing for new curatorial interpretations of your oeuvre.

- You are engaging in estate planning and require a comprehensive, legally sound documentation of your life’s work for valuation and distribution.

Key Takeaways

- Frame your exhibition not as a story, but as a rigorous ‘visual thesis’ with a central, defensible argument.

- Use ‘hero images’ as evidentiary anchors to introduce your thesis and sequence your other works to create a deliberate ‘visual rhythm’ of emotional peaks and valleys.

- The strongest unifying element is a ‘conceptual bind’—an underlying idea—which is more powerful than relying on consistent subject matter or visual style alone.

From Visual Thesis to Physical Reality: Executing Your Curated Vision

Developing a strong curatorial thesis is the most critical intellectual exercise in preparing for a solo show. However, this thesis must ultimately be translated from concept into a physical or digital reality. The execution of the exhibition is where the integrity of your visual argument is truly tested. Every practical decision, from venue selection to budget allocation, must be filtered through the lens of your central theme. A theme-first approach radically alters the traditional exhibition planning process, transforming logistical choices into curatorial acts.

In a traditional approach, an artist might book the first available gallery space and then try to fit their work into it. In a theme-first approach, the choice of venue becomes a strategic decision. Does your thesis on industrial decay require a raw, cavernous space, or does your exploration of domestic intimacy demand a small, quiet gallery? Similarly, marketing is no longer a generic blast to a broad art audience. Instead, it becomes a targeted campaign aimed at communities and individuals who have a pre-existing interest in the concepts your work explores—be it architectural theory, environmental activism, or feminist history.

This methodology demands more time and deliberate planning, but it yields a far more cohesive and impactful result. An ideal window of 6 to 12 months allows for the deep development of the theme and ensures all subsequent decisions serve to amplify it. The following table illustrates the fundamental shift in thinking required to execute a truly theme-driven exhibition.

| Aspect | Traditional Approach | Theme-First Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Venue Selection | Book first available space | Choose venue that enhances theme (intimate for personal work, expansive for landscapes) |

| Budget Allocation | Generic line items | Budget includes materials, installation, transport, marketing, insurance – all aligned with thematic needs |

| Timeline | Standard 3-6 months | 6 to 12 months window is ideal, allowing theme development |

| Marketing | General art audience | Targeted to theme-interested communities |

Ultimately, unifying a disparate body of work is an act of intellectual discipline. By adopting the mindset of a curator, you elevate your practice from mere production to critical inquiry. The result is not just a collection of your best photographs, but a powerful, cohesive, and unforgettable exhibition that solidifies your unique voice in the art world. To begin this process, you must first define your own visual thesis and select the works that will prove it.

Frequently Asked Questions About Curatorial Theme Development

How can I test if my written theme matches my visual work?

Write directly and in an active voice. As suggested by the CUE Art Foundation’s curatorial tips, phrasing like “The exhibition addresses ______” is much stronger than using conditional or passive language. You must be able to answer clearly and confidently: What is this project about? How is my specific approach innovative or insightful? Then, present the text and the work to a trusted colleague and ask if the connection is self-evident.

What makes a curatorial statement weak?

A weak statement relies on passive, descriptive adjectives (e.g., “my work is beautiful,” “the images are melancholic”) rather than strong, active verbs that describe what the work *does* or *questions*. A strong theme is built on verbs and inquiries because these are concepts that can be visually demonstrated, whereas “beauty” is purely subjective.

How specific should my theme be?

Extremely specific. A focused curatorial inquiry makes for a much stronger proposal and a more coherent exhibition than a general or broad theme. A proposal to exhibit “different artists working in oil paint” is weak. A proposal to exhibit artists who use oil paint to “explore the materiality of memory” is strong. The same principle applies to your own solo work: specificity is the foundation of a powerful visual thesis.